COVID-19 Tracheostomy and Mechanical Ventilation

Overview of COVID-19 and Mechanical Ventilation

Approximately 20-30% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and pneumonia have required intensive care for respiratory support (Huang, et al 2020; Wang et al, 2020). Critically ill patients were older (median age 66 years versus 51 years), and were more likely to have underlying co-morbid conditions (72% versus 37%) in comparison to non-ICU patients with COVID-19 (Wang et al, 2020). Among critically ill patients admitted to an intensive care unit, 11–64% received high-flow oxygen therapy and 47-71% received mechanical ventilation; some hospitalized patients have required advanced organ support with endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation (4–42%)(CDC, 2020). The most common diagnosis of severe COVID-19 is pneumonia (World Health Organization, 2020).

Reported illnesses have ranged from mild symptoms to severe illness and death for confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases. Symptoms include fever, cough and shortness of breath. In a report of 1,482 hospitalized patients with confirmed COVID-19 in the United States, the most common presenting symptoms were cough (86%), fever or chills (85%), and shortness of breath (80%), diarrhea (27%), and nausea (24%). Other reported symptoms have included, but are not limited to, sputum production, headache, dizziness, rhinorrhea, anosmia, dysgeusia, sore throat, abdominal pain, anorexia and vomiting (NIH, 2020).

Risk factors associated with respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation are not clearly described in published reports, although from the limited available data, risk factors associated with a critical illness/ICU admission included older age (>60 years), male gender, and the presence of underlying comorbidities (Critical Care Guideline, 2020). Comorbidities associated with severe illness and mortality include:

- Cardiovascular disease

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Chronic lung disease

- Cancer

- Chronic kidney disease

Below is a 3D rendering of a COVID-19 patient’s lung. Lung damage is diffuse and broad throughout the lung.

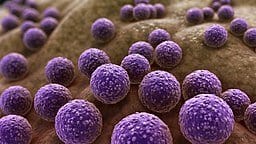

Infection Prevention for Covid-10 and tracheostomy and/or mechanical ventilation

Preventing the spread of COVID-19 is a priority and responsibility for everyone. Healthcare workers around the globe are fighting to slow the spread of the disease. Infection control measures are paramount to protecting workers and patients.

The World Health Organization has guidance on infection prevention and control which will be summarized here. It indicates to initiate infection prevention and control at the point of entry of the patient to hospital. Screening should be done at first point of contact at the emergency department or outpatient department/clinics. Patients should wear a mask, covering the mouth and nose and maintain social distancing. Taking temperatures at the door is also recommended.

Standard Precautions assume that every person is potentially infected or colonized with a pathogen that could be transmitted in the healthcare setting. Healthcare professionals entering the room of a patient with known or suspected COVID-19 should adhere to standard precautions and wear a respirator, gown, gloves and eye protection. Evidence supports that aerosolized transmission risks should be taken at all times. This is also supported by the rate of transmission. Airborne measures refer to a certain diameter size (MMMAD). Droplets can still become aerosolized and travel beyond 6-feet. While there are PPE shortages driving difficult decisions, a high level of protection including N95 masks and above, is recommended for healthcare provider safety.

Hand hygiene is the most effective way to prevent the spread of infection. Hand hygiene signage can be found on the WHO website. Standard precautions also include prevention of needle-stick or sharps injury; safe waste management; cleaning and disinfection of equipment; and cleaning of the environment.

Strict measures should be taken for aerosol generating procedures. Aerosol generating procedures include (but are not limited to) the following:

- Intubation/Tracheostomy

- Noninvasive ventilation

- Bronchoscopy

- Manual resuscitation (bagging)

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (compressions and/or bagging)

- Bronchial hygiene (including open suctioning)

- Proning a patient

- Sputum Induction

- Aerosolized Medications (including nebulizer treatments)

The World Health Care Guidelines indicates the following: “Ensure that health care workers performing aerosol-generating procedures use the appropriate PPE, including gloves, long-sleeved gowns, eye protection, and fit-tested particulate respirators (N95 or equivalent, or higher level of protection). A scheduled fit test should not be confused with a users’ seal check before each use. Whenever possible, use adequately ventilated single rooms when performing aerosol-generating procedures, meaning negative pressure rooms with a minimum of 12 air changes per hour or at least 160 L/second/patient in facilities with natural ventilation. Avoid the presence of unnecessary individuals in the room. Care for the patient in the same type of room after mechanical ventilation commences.” (WHO, 2020).

Other infection precautions include use of dual limb ventilator circuitry with filters placed at the exhalation outlets as well as heat moisture exchange (HME) systems rather than heated humification of single limb circuits.

It is essential that all hospitals and health systems develop task forces to manage patients admitted with COVID-19. The task force involves, but is not limited to designating COVID-19-specific intensive care units (ICUs) and ICU teams, creating back up and expanded staffing schedules, utilizing detailed protocols for infection prevention and medical management, accessing research trials for patients with COVID-19, ensuring adequate personal protection equipment (PPE) supplies and training, forecasting demand, and prioritizing diagnostic lab testing.

Endotracheal intubation and Covid-19

Information regarding management of COVID-19 patients is rapidly changing. Please check the literature and resources below for continued updated information. Mortality could be as high as two thirds among patients with COVID-19 who require ventilation, data from the United Kingdom’s Intensive Care National Audit and Research Center (ICNARC) show.

Some patients with COVID-19 may develop Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), may desaturate quickly during intubation. Pre-oxygenate with 100% FiO2 for 5 minutes. For patients previously on high flow oxygen, some experts switch to 100% non-rebreather. Rapid sequence intubation is appropriate after an airway assessment that identifies no signs of difficult intubation.

- Consider intubation kits and checklists.

- Intubation is an aerosolizing generating procedure and high risk for exposure requiring airborne measures to be taken. Personal protective equipment must be used including a mask (N95 or higher, gown, gloves, goggles/face shield).

- Intubation should be performed in an airborne infection isolation room, if possible.

- There should be the least number of people in the room possible with the door closed during intubation and for a period after.

- Intubation should be performed by the most qualified individual since delayed intubation with multiple attempts may prolong dispersion of aerosols and place the patient at risk of a respiratory arrest. 2-person confirmation of the ET tube passing through the vocal folds with video laryngoscopy is recommended.

Mechanically Ventilated Adults and Pediatrics with ARDS

Some patients with coronavirus may develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). However, while some patients with COVID-19 meet the criteria for ARDS, this may be the minority of patients. Therefore physicians are questioning whether standard respiratory protocols for Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) are the best approach for treating patients with COVID-19. Protocol driven ventilator use may be causing significant ventilator associated lung injury in COVID-19 patients.

- Most experts agree that proning has been beneficial. For adult patients with severe ARDS, prone ventilation for 12–16 hours per day is recommended. Remarks for adults and children: Application of prone ventilation is strongly recommended for adult patients, and may be considered for pediatric patients with severe ARDS but requires sufficient human resources and expertise to be performed safely, protocols (including videos) are available (https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1214103). There is little evidence on prone positioning in pregnant women. Pregnant women may benefit from being placed in lateral decubitus position (WHO, 2020).

- For mechanically ventilated adults with COVID-19 and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), the Panel recommends using low tidal volume (Vt) ventilation (Vt 4–8 mL/kg of predicted body weight) over higher tidal volumes (Vt >8 mL/kg) (NIH, 2020).

- Use a conservative fluid management strategy for ARDS patients without tissue hypoperfusion. Remarks for adults and children: This is a strong guideline recommendation; the main effect is to shorten the duration of ventilation. See reference for details of a sample protocol (WHO, 2020).

- Avoid disconnecting the patient from the ventilator, which results in loss of PEEP and atelectasis (WHO, 2020).

- Use in-line catheters for airway suctioning and clamp endotracheal tube when disconnection is required (for example, transfer to a transport ventilator) (WHO, 2020).

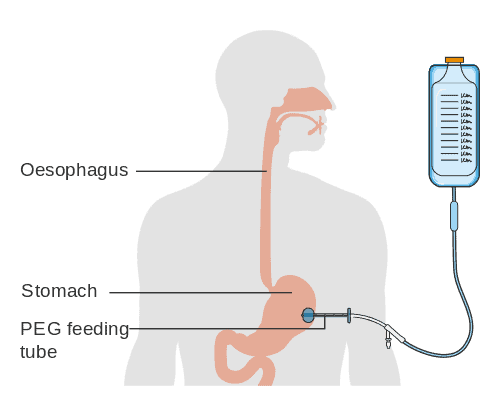

For patients who fail weaning, a tracheostomy may be indicated. Tracheostomy is considered a high risk procedure for aerosolization. Decisions regarding the requirement for tracheostomy in critically ill COVID patients should not be taken lightly, balancing the risks and burdens to both patients and staff.

Tracheostomy during COVID-19 pandemic

Tracheostomy is a high risk procedure for patients with COVID-19 and is considered an aerosol generating procedure (AGP). Aerosol generating procedures are associated with high droplet and particle generation, placing healthcare providers at increased risk for transmission of respiratory viral infections. Aerosol generating procedures should be minimized as much as possible to prevent the spread of infection. During the 2003 SARS outbreak, a systematic review of aerosol generating procedures (tracheal intubation, tracheostomy, non-invasive mechanical ventilation, manual ventilation before intubation) found an increased risk in healthcare workers performing these procedures (Tran JK, et al, 2012). However tracheostomy may be suitable for long term mechanical ventilation needs.

Patients with tracheostomy may be infectious for longer periods if the patient received a tracheostomy due COVID-19 and therefore were critically ill. Critically ill patients are associated with an increase in viral RNA clearance.

Whether or not to perform a tracheostomy in patients with COVID-19 should balance the risk and benefits to the patients and staff. Although tracheostomy is a high risk procedure for aerosolization, failed extubation is also a risk as well as risks of complications of prolonged translaryngeal intubation. Medical practitioners should also take into consideration that if an intubated patient with COVID-19 has been extubated, some may be at high risk of reintubation, require high-flow oxygenation, or non-invasive ventilation, which are aerosol generating. These therapies may also limit the patient’s discharge to lower levels of care.

A survey of ENT surgeons regarding tracheostomy during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that the percentage of patients who had a tracheostomy performed was on average 9.65% (range 0%-100%) with a tracheostomy performed following intubation at an average of 14.4 days (range 7-21). Patients were successfully weaned post tracheostomy on average after 7.4 days (range 1‐16 days). Despite undergoing a tracheostomy, on average 13.5% of patients died (drawn from 14 respondents from a population of 1687 intubated and ventilated patients) (D’Souza, A et al, 2020). However, more recently in the UK, a team performed 61% tracheostomy rate amongst 164 patients who were intubated due to COVID-19 during a 6 week reporting period (McGrath, B, Brenner, M., Warrillow, S, 2020).

Findings from a recent review, (Dawson, R, et al, 2021), found that the same basic principals of care should apply to a patient with known or suspected COVID-10 as for any other patient with a tracheostomy.

Benefits of Tracheostomy and Covid-19

Benefits of tracheostomy during COVID-19 is that tracheostomy may accelerate weaning. Faster weaning can free up ventilator equipment, careproviders, and higher acuity beds.

Another significant benefit is that the patient will be in a closed system. When the cuff is inflated airflow and aerosols are maintained within the tubing. It also offers the ability to reduce sedation requirements, which can reduce sedation related delirium, improve patient comfort, provide less intensive nursing care and potentially a lower level of care. Prolonged intubation may also be related to increased laryngeal injury including tracheal stenosis, edema, vocal fold paresis or paralysis, desensitisation, dysphagia, dysphonia, or erythema.

Percutaneous, Surgical or Hybrid Tracheostomy?

If the medical team determines that a tracheostomy is necessary, there is debate over whether a percutaneous or surgical procedure is less aerosol generating, with local factors, expertise and competencies influencing the decision. Those performing tracheostomy are recommended to use the techniques and equipment that they are familiar and experienced in using (McGrath et al, 2020).

Whether percutaneous or surgical, it is best practice to perform the procedure in an ICU room or operating room, preferably a negative pressure room. Reduce the team members to only essential personnel and only the most experienced staff to perform the procedure to provide efficiency. Rehearse the procedure and consider simulated procedures.

All appropriate airborne PPE should be used during the tracheostomy procedure. Experts suggest the use of enhanced PPE with PAPRs, eye protection, fluid-repellent disposable surgical gown and gloves. If a PAPR is not available, the use of fit tested filtering face piece 3 (FFP3) or N95 mask with an additional fluid shield.

During the tracheostomy procedure, establish complete paralysis using neuromuscular blockade to prevent coughing and aerosol dispersion (Heyd, et al, 2020). Procedure steps for surgery for a tracheostomy are outlined in A surgical safety checklist for performing tracheostomy in Covid-19 patients. The ENT_UK is another surgical guideline. In a single center study, percutaneous tracheostomy was performed with a protocol to use periods of apnea when disconnecting the ventilator circuit. All physicians were Covid-19 negative following the procedures (Boujaoude, Z. et al., 2021).

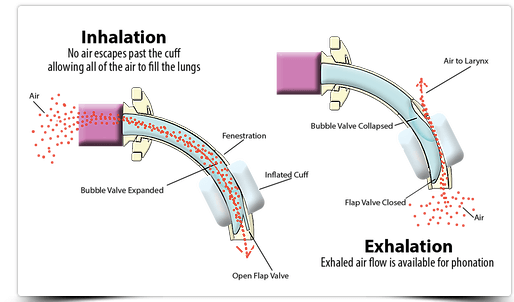

Another recommendation is to only use cuffed, non-fenestrated tracheostomy tubes during the procedure and for any tracheostomy changes until the patient is confirmed Covid negative. The inflated tracheostomy cuff offers a closed system to help prevent cross contamination of staff. The size of the tracheostomy tube should be considered and is particularly important during Covid-19 as the smaller size of a stoma can reduce aerosol generation, reduce tracheostomy tube changes and reduce leakage around the cuff.

Further details for management of patients with tracheostomy during COVID-20 can be found on the National Tracheostomy Safety Project and the American Academy of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery.

Timing of Tracheostomy for Covid-19

The decision to perform tracheostomy should include potential risks and benefits for the patient, risks of infection spread to health-care workers, other patients and family and available health-care resources. Criteria has included failed extubation, a failed sedation hold, and anticipated prolonged respiratory wean (McGrath, B, Brenner, M, Warrillow, S, 2020).

- A multidisciplinary expert opinion recommended that tracheostomy be delayed until at least day 10 of mechanical ventilation and considered only when patients are showing signs of clinical improvement to tolerate the procedure. The consensus did not recommend tracheostomy in patients who still need high fractions of inspired oxygen, have high ventilator requirements, and might require prone positioning as part of their ventilatory strategy (McGrath, B., 2020). Prone positioning is more difficult to achieve for patients with tracheostomy due to a higher risk of dislodgement, displacement or occlusion.

- According to the Airway and Swallowing Committee of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (April, 2020):

“Avoid tracheotomy in COVID-19 positive or suspected patients during periods of respiratory instability or heightened ventilator dependence.”

“Tracheotomy can be considered in patients with stable pulmonary status but should not take place sooner than 2-3 weeks from intubation and, preferably, with negative Covid-19 testing. BAL is the most sensitive means of testing and is recommended for intubated patients to determine viral clearance. One proposed policy is two consecutive negative PCR tests 24 hours apart. However, universal testing may not be feasible due to the availability of testing and constraints for time. Any critically ill patient recovering from COVID-19 pneumonitis is considered high risk of infection to staff during tracheostomy insertion. Full airborne PPE precautions should be adhered to during all tracheostomy procedures during the Covid-19 pandemic and adhere to strict donning and doffing of PPE.

Timing of Tracheostomy- evolving

Timing of tracheostomy is evolving since the beginning of the pandemic. Many facilities are opting for earlier tracheostomy than originally recommended. There must be a balance between delaying insertion during the patient’s most infected period due to potential risks to staff from aerosolization versus the complications of prolonged intubation.

The Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham COVID-19 airway team published in the British Journal of Anesthesia, that tracheostomy timing was not influenced by SARS-CoV-2 test results, which have been used in some protocols for candidacy for tracheostomy. “At the onset of the pandemic there were rightly concerns over the risks to staff from performing tracheostomy in patients still considered infectious. However, using upper respiratory tract viral polymerase chain reaction tests alone to determine infectivity and associated risks to staff is unreliable.” The same team performed most of the tracheostomy and none reported symptoms of coronavirus during the study period.

Other studies from large centers or hospital groups are also reporting tracheostomy for COVID-19 patients as less than the delayed timeframe proposed by earlier guidelines. A large Spanish study reported that from 1980 patients, the medium time to tracheostomy was 12 days (Martin-Villares, C. et al., 2020).

Complications after intubation and tracheostomy

Due to the prolonged intubation periods, there have been reports of a high incidence of laryngeal injury including vocal fold paralysis, posterior glottic stenosis and subglottic stenosis (Meister, K. et al., 2020). Secretions have been thick and tenacious, which can lead to tracheostomy tube occlusions. Furthermore the cuff of the tracheostomy tube is often over-inflated to prevent aerosol generation. Cuff overinflation can cause complications such as tracheamalacia and long term effects such as subglottic or tracheal stenosis.

Tracheostomy management of Covid-19 patients for ventilated and non-ventilated patients

For patients who already had a tracheostomy tube in place, management and care of the tube is important in preventing Covid-19. For patients with a tracheostomy tube who present with Covid-19, it is important to reduce the spread of infection to other healthcare workers and patients. All healthcare workers should follow PPE and airborne/droplet precautions according to institutional guidelines. For emergencies, PPE should still be worn.

Monitor Cuff Pressures:

Monitor cuff pressures regularly to prevent tracheal injury. Ideally cuff pressure should be between 20-30cmH2O. Adequate cuff pressure is critical to avoid cuff leakage and aerosolization in patients with active Covid-19. However, unnecessary high cuff pressure can result in tracheal necrosis and potentially lead to stenosis. When checking cuff pressures with a manometer the cuff may deflate and leak, resulting in aerosol generation. PPE should be worn whenever the cuff is checked.

Suctioning:

In early post-mortem studies of positive Covid-19 patients, profuse viscous secretions were observed in the respiratory tracts. Aggressive pulmonary hygiene is recommended including tracheal suctioning and subglottic suctioning.

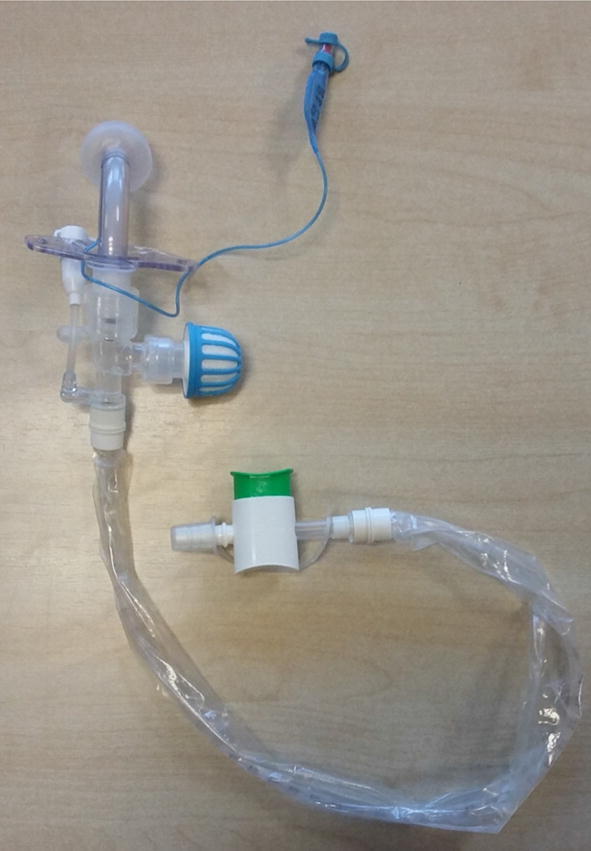

If the patient is able, encourage the patient to perform self tracheostomy care including suctioning. If the patient is able to perform self suctioning, staff can exit the room during suctioning to reduce personnel in the room during an aerosol generating procedure. Closed suctioning is mandatory for patients with Covid-19 to prevent disconnecting from the circuit to prevent aerosolization.

Humidification:

Humidification is critical for patient care. The tracheostomy bypasses the upper airway for humification, filtration and warming. A simple heat and moisture exchanger is recommended to provide humidification and does not generate aerosols. Active water-based humidification should be assessed for on an individual basis for thick secretions. Hydration and mucolytic needs should be addressed to minimize the risk of occlusion from thick secretions.

Nebulizers:

Nebulizers increase the risk of aerosolization and transmission of infection to healthcare providers and are therefore not recommended for non-intubated patients during the Covid-19 pandemic. The use of metered-dose inhalers are preferred where possible.

Tube Changes and Cleaning Inner Cannula:

Avoid tube changes, ideally until patients are not infectious, unless there is a cuff failure or emergent issue. Use an inner cannula if secretions are thick or in an open system. If inner cannulas are used, limit inspection/cleaning of the inner cannula to prevent opening the circuit which results in aerosol generation. Change the inner cannula when the circuit is broke for other reasons. Disposable inner cannulas have been recommended so that there is no concern for contamination of other materials when a nondisposable inner cannula is cleared.

Frequency of Trach Care:

The frequency of tracheostomy care including suctioning, humidification checks, stoma care can be viewed on this table by the National Tracheostomy Safety Project.

Cuff Deflation:

Cuff deflation is aerosol generating and risks and benefits should be reviewed. Cuff deflation can increase aerosolization because it frequently results in coughing. If cuff deflation is completed in a COVID positive patient, it should be done in a private room or in a designated cohorted COVID area (McGrath, B et al, 2020). Proper airborne PPE should be worn during cuff deflation trials for weaning. Patients should wear face masks and tracheostomy masks/shields to reduce risks of aerosols.

Speaking Valves:

Speaking valves can increase the potential for coughing which can result in aerolization. Therefore appropriate PPE should be worn. Patients should wear face masks during speaking valve use. A humidification bib can be placed over the tracheostomy tube and speaking valve for filtering the air to help protect the patient. Once a speaking valve is placed, exhaled air is redirected out the nose and mouth. Therefore face masks should be worn.

Ventilated patients and Covid-19

For ventilated patients who are Covid-19 positive, unknown or suspected:

- Cuffed, non-fenestrated tracheostomy tubes should be used and remain inflated to limit aerosol generation

- Avoid disconnecting patient circuit from ventilator. If necessary, clamp tubing distal to HME filter prior to disconnecting.

- Use inner cannula if thick secretions or on open system. If used, limit inspection/cleaning of inner cannula.

- Cuff deflation when weaning from ventilator will result in aerosol generation. Ensure patients are in isolation or in a cohort room with other COVID-19 patients. Have the patient wear a face mask during cuff deflation to reduce the likelihood of transmission.

- To place a speaking valve in-line with the vent, the circuit must be broken. Ensure appropriate PPE as this can produce aerosols. Have the patient wear a face mask to reduce the likelihood of transmission.

Non-Ventilated patients and Covid-19

For non-ventilated patients who are Covid-19 positive, unknown or suspected:

- Cuffed, non-fenestrated tracheostomy tubes should be used and remain inflated to limit aerosol generation.

- Humidification with a simple HME device, along with a viral filter should be placed on the tracheostomy tube.

- A simple facemask should be placed on the patient. Patients not on a closed ventilation circuit should also wear a surgical mask over their stoma if tolerated to potentially decrease the spread of droplets from the stoma.

- Suctioning should be performed with a closed suction system.

- Cuff deflation when weaning from ventilator will result in aerosol generation. Ensure patients are in isolation or in a cohort room with other COVID-19 patients. Have the patient wear a face mask during cuff deflation to reduce the likelihood of transmission.

- If using a speaking valve, have the patient wear a face mask to reduce the likelihood of transmission.

- Patients not on a closed ventilation circuit should also wear a surgical mask over their stoma

Tracheostomy Outcomes for Covid-19

A recent study analyzed data from a Covid-19 cohort of patients who received a tracheostomy. Thirty day survival was significantly improved in patients receiving tracheostomy and early tracheostomy (within 14 days of intubation) was associated with shortened ICU length of stay (McGrath, B, Brenner, M, Warrillow, S, 2020). However, the results were not blinded, leaving room for selection bias.

Summary

The role of tracheostomy during the Covid-19 pandemic is evolving. Tracheostomy is an aerosol generating procedure and healthcare workers must protect themselves with strict airborne precautions. Information regarding guidelines and standards are continuing to emerge. The reader is encouraged to seek the resources below for further information regarding tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation.

Resources for Covid-19 and tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation

Mechanical Ventilation for COVID-19 through AARC with edX and Harvard is a free online introductory course on ventilator use that address the urgent need for medical professionals during the pandemic. The course does not replace the expertise of a critical care respiratory therapist, rather it provides foundational knowledge that will allow collaboration for the best possible patient care in a crisis situation.

The American Heart Association (AHA), in conjunction with the American Association of Respiratory Care and the American Society of Anesthesiologists, has published four training modules designed to teach healthcare professionals the basics of oxygenation and ventilation management for COVID-19 patients.

NIH Guideline for Covid-19– A guideline based on expert opinion and scientific evidence with recommendations including mechanical ventilation, infection control, drug therapy and hemodynamics. This guide will be updated with changes.

The World Health Organization has issued guidelines for the clinical management of severe acute respiratory infections for those that COVID-19 disease is suspected. There are recommendations for oxygen therapy, management of acute respiratory distress syndrome including mechanical ventilation, tidal volumes, prone ventilation and PEEP levels.

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: Guidelines on the Management of Critically Ill Adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a guideline to provide recommendations to support hospital clinicians managing critically ill adults with COVID-19 in the intensive care unit (ICU). As evidence is emerging that many patients with COVID-19 do not have typical ARDS, make recommendations based on the individual characteristics. The link includes information on infection control, testing, and supportive care (hemodynamic support, fluid therapy, vasoactive agents, ventilatory support, invasive ventilation, and therapy).

The EVMS Critical Care Covid-19 Management Protocol. This is the EVMS recommended approach to COVID-19 based on their consideration of the best (and most recent) available literature. Information regarding COVID-19 as not a typical presentation for ARDS.

The Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society has provided guidelines for COVID-19. Guidelines include ICU planning such as measures to reduce ICU demand and increasing the infrastructure. Infection control strategies for testing, isolation and PPE are reviewed.

The CDC has put in place infection prevention and control recommendations for patients with suspected or confirmed coronavirus disease in healthcare settings through limiting germs, isolating infected patients and protecting healthcare professionals through hand hygiene and appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE). There is a shortage of PPE in the United states for masks, gloves and gowns during this epidemic. The CDC also has some recommendations to optimize PPE and extend supplies.

The National Tracheostomy Safety Project in the UK has also issued some guidance for management of patients with tracheostomy during the coronavirus outbreak. The recommendations include information regarding where to manage patients with tracheostomy, strategies for the actual tracheostomy procedure, and then mechanically ventilated versus spontaneously breathing patients.

We will continue to update this resource page. However, information surrounding the coronavirus disease has been changing. Please continue to check on the references for further information. See references below.

References:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020.

Gattinoni L. et al. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatment for different phenotypes? (2020) Intensive Care Medicine; DOI: 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2

Martin-Villares C, Perez Molina-Ramirez C, Bartolome-Benito M, Bernal-Sprekelsen M; COVID ORL ESP Collaborative Group (*). Outcome of 1890 tracheostomies for critical COVID-19 patients: a national cohort study in Spain [published online ahead of print, 2020 Aug 4]. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;1-8. doi:10.1007/s00405-020-06220-3

McGrath, B. A., Wallace, S., & Goswamy, J. (2020). Laryngeal oedema associated with COVID-19 complicating airway management. Anaesthesia, 75(7), 972-972. doi:10.1111/anae.15092

National Tracheostomy Patient Safety Project, 2020.

Portugal LG, Adams DR, Baroody FM, Agrawal N. A Surgical Safety Checklist for Performing Tracheotomy in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 28]. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;194599820922981. doi:10.1177/0194599820922981

Rovira A, Dawson D, Walker A, et al. Tracheostomy care and decannulation during the COVID-19 pandemic. A multidisciplinary clinical practice guideline [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 17]. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;1-9. doi:10.1007/s00405-020-06126-0

World Health Organization, 2020. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected.

Zhonghua, Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. Expert concensus on preventing nosocomial transmission during respiratory care for critically ill patients infected by 2019 novel coronavirus. 2020 Feb 20;17(0):E20.doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn1001-0930.2020.0020

Responses