Tracheal Stenosis and Intubation or Tracheostomy

Tracheal Stenosis: Overview

Tracheal stenosis in a narrowing of the airways which can occur at the larynx, tracheastoma, or below the larynx (subglottic). It can occur congenitally or acquired.

Stenosis is considered congenital if there is no history of prior endotracheal intubation or any of the causes of acquired stenosis. It is the 3rd most common congenital disorder of the larynx.

Acquired tracheal stenosis is more common than congenital. The incidence rate of tracheal stenosis following laryngotracheal intubation and tracheostomy has been said to range from 6% to 21% and 0.6% to 21%, respectively (Farzanegan, 2016). It is a rare, but serious complication.

Causes of Tracheal Stenosis

Acquired tracheal stenosis, including subglottic stenosis is most often caused by prolonged endotracheal intubation. The risk of ischemic injury resulting in stenosis is higher with the duration of intubation (greater than 10 days), but it has also been reported in brief intubations (Li, M., 2018).

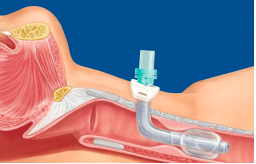

Tracheal stenosis due to intubation can occur anywhere from the endotracheal tube tip to the glottic and subglottic area. It is mostly commonly at the site of the inflatable cuff of the endotracheal or tracheostomy tube or at the stoma site. When the stenosis is at the stoma site, it is typically from abnormal wound healing with excess granulation tissue formation around the tracheal stoma site and frequently there is an associated cartilage fracture or tracheomalacia of the trachea wall. There is a higher risk for tracheal stenonosis with a high tracheostomy site at, or just inferior to, the cricoid arch, or to malposition of an endotracheal tube cuff. Larger bore endotracheal tubes also pose an increase risk of laryngeal injury.

Over-inflation of the cuff can result in tracheal necrosis and eventual tracheal stenosis. Management of cuff pressures is crucial in preventing tracheal injury. Cuff pressure of ≥30 mm H2O were associated with greater rates of tracheal stenosis. Cuff pressures should be maintained between 20-30cmH2O. High volume-low pressure cuffs are also more likely to reduce the risk of tracheal injury.

Surgical variables associated with increased stenosis included placement of a tracheostomy tube greater than size 6, use of percutaneous technique, and failure to create a Bjork flap (Li, M., 2018). Stenosis can also be caused from trauma, tracheal tumor or compression of the trachea by a tumor.

Other factors predisposing patients to tracheal stenosis include excessive corticosteroid steroid usage, advanced age, female and estrogen effect, severe respiratory failure, severe reflux disease, autoimmune diseases (Wegener’s granulomatosis, sarcoidosis and others), obesity, keloids, obstructive sleep apnea, and radiation therapy for oropharyngeal and laryngeal cancer (Kastanos, N., 1983; Kashkoreva, 2007; Chang, E., 2019)

Grading

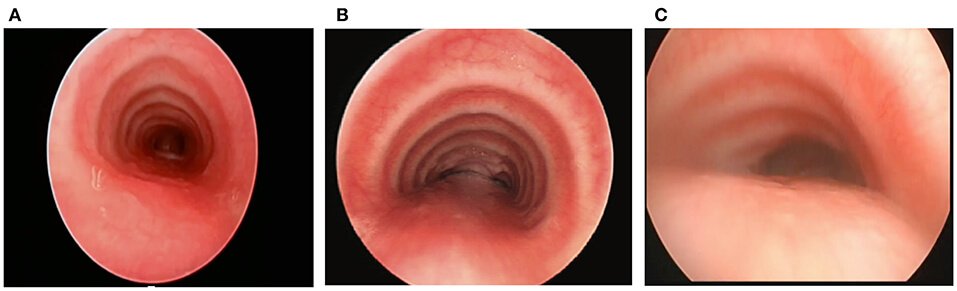

The severity of tracheal stenosis can be measured with the Cotton-Myer grading system for subglottic stenosis. It can be used to describe tracheal obstruction as well.

- Grade 1 – 0-50% obstruction

- Grade 2 – 51-70% obstruction

- Grade 3 – 71-99% obstruction

- Grade 4 – No detectable lumen

The modified Cotton-Myer grading scale is based on the percentage of obstruction calculated by passing an endotracheal tube through the stenosis resulting in approximation of the stenotic diameter divided by the age-appropriate endotracheal tube size.

McCaffrey offers an alternate classification system that encompasses laryngotracheal stenosis.

Symptoms of Tracheal Stenosis

Symptoms of tracheal stenosis are closely related to the degree of narrowing. The individual may be asymptomatic in mild cases of stenosis, until an upper respiratory tract infection occurs. Symptoms may then include respiratory distress or stridor (noisy breathing during inhalation). Other symptoms include apnea, chest congestion and pneumonia. Prolonged or recurrent episodes of croup is suspicious for tracheal stenosis. Ten percent of patients with benign stenosis may be undiagnosed for more than ten years or even incorrectly treated for asthma (Farzanegan, R et al (2017).

“It has been demonstrated that the expiratory disproportion index, defined as the ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 s to peak expiratory flow rate, has a great clinical utility in differentiating LTS from other respiratory diseases” (Piazza, C. et al 2020).

Tracheal stenosis is a possible indication for tracheostomy if the airway is obstructed, resulting in difficulty breathing.

Diagnosis of Tracheal Stenosis

The diagnosis of tracheal stenosis may include one or more of the following tests:

- Airway fluoroscopy

- Bronchoscopy

- CT with 3‐D reconstruction

- Echocardiogram

- Laryngoscopy

Tracheal Stenosis Treatment

Treatment of tracheal stenosis varies depending on the severity and can include either endoscopic or open approaches. Often, endoscopic approaches such as dilatation or endoscopic scar excision are attempted for stenosis of Myer‐Cotton Grades I and II. It is imperative that causes of laryngeal inflammation (such as uncontrolled laryngopharyngeal reflux) be appropriately managed and controlled prior to surgical treatment. Grade III and IV usually require open surgery such as laryngotracheoplasty, laryngotracheal reconstruction, cricotracheal resection or slide tracheoplsty. Repeated treatments are often needed.

During Covid-19, treatment alternatives may be considered. See below for more information.

A tracheostomy tube can bypass the stenosis to enable a patent airway. A longer tracheostomy tube may be required to bypass the level of stenosis, such as a Shiley XLT Distal. The distal length tube is an appropriate choice as it is longer in the airway compared to the Shiley XLT Proximal which is appropriate for patients with thick neck circumference.

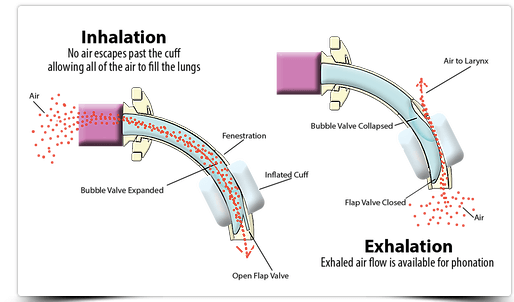

Speaking Valves or Capping for Tracheal Stenosis

Tracheal stenosis is not an absolute contraindication for speaking valves or capping use. A one way speaking valve works by allowing inspiration to occur through the tracheostomy tube and exhalation through the upper airway. In mild or even moderate forms of tracheal stenosis, the individual may be able to exhale around the tracheostomy tube and through the upper airway without respiratory distress. If there is difficulty breathing or significant changes in vital signs with a speaking valve or cap, then the device should be removed. A skilled clinician should assess the safety of using a speaking valve or cap. The cuff of the tracheostomy tube must be fully deflated prior to placement.

Sometimes the tracheostomy tube may obstruct a stenotic segment that, without the tube, the airway may be open enough to breathe without requiring surgery. The tube may need to be downsized to increase the space that the patient can exhale.

The image below shows a Shiley #6 taking up much of the space of the airway. The tube was downsized to a size #4, allowing for some exhaled airflow through the upper airway for improved breathing with a speaking valve/capping.

Check out our article for more information on different types of speaking valves.

Tracheal Stenosis and Covid-19

Tracheostomy is often delayed for patients with COVID-10 until the patient no longer requires prone positioning and the patient has been cleared of the virus. Patients are therefore often orally intubated for prolonged periods of time, for up to 3-4 weeks. This is much longer than pre-pandemic, when a tracheotomy was typically performed following 7-14 days of intubation. The prolonged intubation is a high risk for tracheal stenosis and laryngeal injury.

A tracheotomy may be performed on patients with COVID-19 or recovering from COVID-19 for long term means of mechanical ventilation and weaning. A cuffed, non-fenestrated tracheostomy tube is recommended in order to reduce aerosolization. When the cuff is inflated, there is a closed system in place. Air flows in and out of the tracheostomy tube, connected to ventilator tubing, so that respiratory droplets and aerosols remain inside the tubing. The closed system reduces the likelihood of spreading infection of COVID-19 or other infections.

When there is a leak in the system (such as if the cuff is not completely sealed against the tracheal wall), there is a risk of aerosolization. Aerosols can remain in the air for up to 3 hours for Sars-Cov2. Therefore some healthcare workers have been trained in preventing a leak for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 by inflating the cuff until there is no leak and without regard to the cuff pressures. Cuffs may be overinflated past the recommended cuff pressures to maintain a “sealed” airway. Recommended cuff pressures are between 20-30cmH2O. When cuff pressure is greater than or equal to 30cmH2O there is a high risk of injury to the tracheal wall and thus potential stenosis.

Treatment of tracheal stenosis is often dilation or surgical. There are high viral concentrations in the upper aerodigestive tract for patients diagnosed with Covid-19, potential to spread with asymptomatic carriers and aerosolization during airway procedures. This provides a high risk for healthcare workers. Dilation and surgical techniques are highly aerosolizing and should be avoided with patients with COVID-19 or suspected COVID-19. If testing for COVID-19 is not adequate, alternative airway management techniques and safety measures can be taken.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, tracheal stenosis surgery should be performed when delay poses significant risk to the patient. When visualization of the larynx is required, appropriate airoborne precautions should be in place. Even if a test is negative for Covid full airborne precautions PPE should be worn at this time. The guiding principal is mitigation of viral aerosolization by using closed systems, rapid sequence induction, neuromuscular blockade and avoiding bag-mask ventilation (Prince, A, 2020).

Check out our article on COVID-19 and Tracheostom

Summary

Although rare, tracheal stenosis is a serious complication that may require surgical treatment when severe. Due to the emerging issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic, there may be an increase in tracheal stenosis. It has many causes and may lead to a tracheostomy tube in order to bypass the stenosis for breathing. Stenosis may also be a complication from the prolonged intubation, tracheostomy procedure or cuff overinflation. Practitioners should be aware of the symptoms of tracheal stenosis and management. Tracheal stenosis can be misdiagnosed as asthma or other pulmonary disorders, therefore delaying appropriate interventions.

Related Courses:

Resources

Chang E, Wu L, Masters J, et al. Iatrogenic subglottic tracheal stenosis after tracheostomy and endotracheal intubation: A cohort observational study of more severity in keloid phenotype. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2019;63(7):905-912. doi:10.1111/aas.13371

Farzanegan R, Feizabadi M, Ghorbani F, Movassaghi M, Vaziri E, Zangi M, Lajevardi S, Shadmehr MB. An Overview of Tracheal Stenosis Research Trends and Hot Topics. Arch Iran Med. 2017 Sep;20(9):598-607. PMID: 29048922.

Koshkareva Y, Gaughan JP, Soliman AM. Risk factors for adult laryngotracheal stenosis: a review of 74 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007;116(3):206-210. doi:10.1177/000348940711600308

Kastanos N, Estopá Miró R, Marín Perez A, Xaubet Mir A, Agustí-Vidal A. Laryngotracheal injury due to endotracheal intubation: incidence, evolution, and predisposing factors. A prospective long-term study. Critical Care Medicine. 1983 May;11(5):362-367. DOI: 10.1097/00003246-198305000-00009.

McCaffrey TV. Classification of laryngotracheal stenosis. Laryngoscope 1992;102:1335-1340

Myer CM III, O’Connor DM, Cotton RT. Proposed grading system for subglottic stenosis based on endotracheal tube sizes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1994;103:319-323.

Prince, A. D. P., Cloyd, B. H., Hogikyan, N. D., Schechtman, S. A., & Kupfer, R. A. (2020). Airway Management for Endoscopic Laryngotracheal Stenosis Surgery During COVID-19. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 163(1), 78–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820927002

Wasserzug O, DeRowe, A. Subglottic Stenosis: Current Concepts and Recent Advances. Int J Head and Neck Surg 2016; 7(2): 97-103.

Responses